Scotland.

Rugged, wild and free.

It’s difficult to summarise a country in just 3 words, but hard pushed, I’d struggle to find a more concise and fitting description.

Those that know me, are aware of how much I love to travel. Italy being my obvious destination of choice. In my opinion, there is nowhere better in comparison, especially if you share my passion for the mountains. But perhaps I should have looked a little closer to home? I am, after all, a fell runner. I was born to run in the hills and mountains of Great Britain. The sport I love was forged in this environment. So what better place to visit than Scotland.

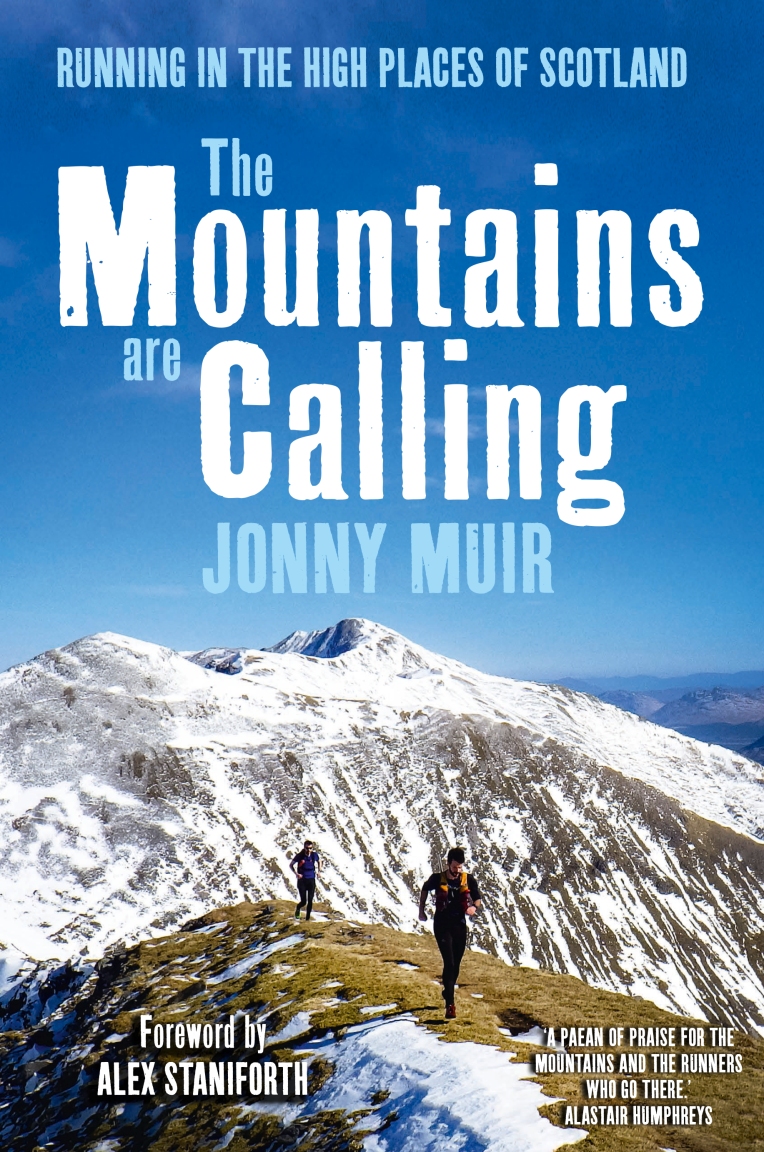

Pictured above: Running in the Isle of Skye (April 2018), with the famous Cuillin ridge looming in the distance.

Pictured above: Running in the Isle of Skye (April 2018), with the famous Cuillin ridge looming in the distance.

Scotland boasts the highest mountains in the UK and has produced some of the greatest ever mountain runners that Britain has ever seen – Angela Mudge, Robbie Simpson, Andrew Douglas and Finlay Wild, to name but a few. So it was something of a New Year’s resolution of mine to discover a little bit more of this amazing country.

In January of 2018, I drove to the Isle of Mull. I was amazed by its beauty and it left me wanting more. In April, I decided to return to the north. I was desperate to see what the rest of the Scottish Islands had to offer and the Isle of Skye was at the very top of my list. It came with a flood of recommendations, my friends would always mention it during conversation. Many legends of our sport have previously graced its rugged landscape. I was treading in the footsteps of giants. No more so than the great Finlay Wild. An 8-times winner of the Ben Nevis fell race and renowned for his fell running prowess. A man with a reputation that proceeds him.

In this adapted extract from The Mountains are Calling, Finlay Wild, Scotland’s pre-eminent hill runner, is attempting to break the record for the fastest traverse of the notorious ridge line of the Black Cuillin.

Pictured above: The great Finlay Wild.

Pictured above: The great Finlay Wild.

Finlay Wild stood on the summit of Sgùrr nan Gillean, the northern culmination of the Black Cuillin of Skye. The scree fountain of Glamaig across the deep trough of Glen Sligachan gleamed in dazzling sunlight; islands punctuated the glittering glass of the Inner Sound; away in the east, Ben Nevis stared impassively. The transcendent world of the so-called Isle of Mist was at harmony. The runner was not. He looked back along the ridge he had just negotiated – an eight-mile scythe of alpine pinnacles and splintered crags, flanked by plunging gullies. There is no greater examination in British mountaineering; it is, as Sir Walter Scott noted, unrivalled in its ‘desolate sublimity’. Finlay – a twenty-nine-year-old GP from Fort William, unknown outside the clique of hill running – had beaten the ‘unbeatable’, becoming the fastest to traverse the ridge, but something did not feel right. Doubt crowded his mind.

Starting from where it had all begun on Gars-bheinn, he traced the twisting blade of the ridge, silently counting mountains. His eyes lingered on Sgùrr Mhic Choinnich, the fourth of the eleven Munro summits. A surge of uncertainty. Finlay pulled out a flip book of summit diagrams, leafing through the pages until he located Sgùrr Mhic Choinnich. He looked hard at the drawing, then raised his eyes to gaze again at the mountain. A very simple question burst from his subconscious: had he touched the pile of stones on the 948-metre highest point? He had certainly climbed the peak; the spine of the central ridge made that unavoidable. The cairn though? Had he put his hand on it?

As Finlay descended, first to a road, then along a glen, the ridge now over his left shoulder, his mind dwelt on that airy crest. While he was unable to convince himself that he had touched the cairn, nor could he be sure he had not. His parents and a group of friends were waiting at Glenbrittle, ready to congratulate him. ‘I wasn’t, “yeah, I’ve done it”,’ Finlay remembered. ‘I said that I’ve kind of done it, but I need to check something. Basically, I got away from there as soon as I could and walked back up to the summit. That gave me time to think: what will I do if I haven’t touched it?’

Finlay clambered into the glaciated bowl of Coire Làgan, where vast chutes of scree cascade from a cirque of astonishing mountains. To the right was Sgùrr Alasdair, the acme of Skye; to the left, the shark’s fin of the Inaccessible Pinnacle; between them was the steep sliver of Sgùrr Mhic Choinnich, its west face forming the gigantic headwall of Coire Làgan. Scrambling up West Buttress, he made directly for the summit. Once on the ridge, the vista opened: mountains were everywhere; the islands of Eigg and Rum reared immaculate from the sea. It was the sort of day when you may have been able to glimpse the dark dots of the St Kilda archipelago, pitched some 100 miles to the west, jostled by the Atlantic swell.

Finlay was only looking to a summit of slabby rocks. Concreted to the cairn on Sgùrr Mhic Choinnich is a sixty-year-old plaque dedicated to climber Lewis Macdonald. Before it was shattered by lightning, a couplet read: ‘To one whose hands these rocks has grasped, the joys of climbing unsurpassed.’ Finlay knew before he got there. Unlike Macdonald, he had not grasped these rocks.

Desperately searching for a reason, Finlay began to piece together what had happened, why it had happened. He had approached the summit on a marginally different line to previous ascents – a common occurrence on the technical ground of the Cuillin. The newness must have momentarily disorientated him. Unconsciously, Finlay ran past the top, his mind already preparing for the difficulties ahead, principally the basalt-rudder of the Inaccessible Pinnacle and the six-storey down-climb from its top.

The summit of Sgùrr Mhic Choinnich had been ten metres away, amounting to a single metre of height gain. ‘Five seconds,’ Finlay said ruefully.

Finlay’s ambitions hinged on a decision of conscience. ‘The weird thing was that I knew I had done it, but at the same time, parallel to that, I knew I couldn’t claim it the way I had done it,’ he said. Finlay could have been excused for erring, for prevaricating. It was five seconds. The oversight was not deliberate. He had done everything else by the book: adhering to a set of standards enshrined by one-time record holder Andy Hyslop, demanding the contender visits the eleven Munros and two further summits, as well as undertaking four technical and exposed sections of rock climbing. Furthermore, to avoid any doubt over the record’s validity, Finlay had been taking splits at every summit on two watches. In races and mountain marathons there are marshals or checkpoints to ensure competitors do not – for want of a better word – cheat.

‘No-one is policing this traverse,’ Finlay said. ‘These things are done on trust. It is totally on your own conscience.’

Ultimately, there was no doubt, no debate. By strict definition, he had not summited Sgùrr Mhic Choinnich. It was five seconds but it could have been one, for if Finlay had not summited Sgùrr Mhic Choinnich, not gone as high as is physically possible, then he had not traversed the ridge. There could be no record. Not today.

It was a gesture that symbolised the ethos of his sport: nothing was more important than doing things the right way.

The Mountains are Calling, by Jonny Muir

Jonny Muir was a nine-year-old boy when the silhouette of a lone runner in the glow of sunset on the Malvern Hills caught his eye. A fascination for running in high places was born – a fascination that would direct him to Scotland. Running and racing, from the Borders to the Highlands, and the Hebrides to the hills of Edinburgh, Jonny became the mountainside silhouette that first inspired him.

His exploits inevitably led to Scotland’s supreme test of hill running: Ramsay’s Round, a daunting 60-mile circuit of twenty-four mountains, climbing the equivalent height of Mount Everest and culminating on Ben Nevis, Britain’s highest peak – to be completed within twenty-four hours.

While Ramsay’s Round demands extraordinary endurance, the challenge is underpinned by simplicity and tradition, in a sport largely untainted by commercialism. The Mountains are Calling is the story of that sport in Scotland, charting its evolution over half a century, heralding its characters and the culture that has grown around them, and ultimately capturing the irresistible appeal of running in high places.

Pictured above: The author, Jonny Muir

Pictured above: The author, Jonny Muir

Jonny Muir is a runner, writer and teacher, and The Mountains are Calling, published by Sandstone Press, is his fourth book. A runner since his school days, Jonny ran and raced on road, track and trail before receiving a calling to the mountains. Since then, he has run extensively in the British hills and mountains, and has completed the Bob Graham Round and Ramsay’s Round.

The Mountains are Calling is available from…

Looks a fab read Ben. Thanks for sharing

LikeLiked by 1 person